Are Shares offering enough of a risk premium over Bonds?

Shares versus bonds

It is generally agreed that to compensate for their greater short term volatility and risk of loss shares should provide a return differential over a ‘risk free’ asset like government bonds over the long term. This return differential is referred to as the equity risk premium (ERP) which is perceived to be around 5% to 7% pa as this is what it has been for much of the post-war period. But thanks to the recent bear market in shares, US shares have underperformed US bonds by 7% pa over the last decade and Australian shares have outperformed bonds by just 2% pa. Does this mean shares are a dud investment? And the equity risk premium concept is meaningless?

The answer to both is no. As the equity risk premium concept relates to the long term, the bear market of the last two years proves nothing about its merits. There is much confusion surrounding the equity risk premium and some of this flows from the fact that it can refer to three different things: the historically realised return gap between equities and bonds, the gap required by investors to attract them to invest in equities, and the prospective (or likely) long-term gap based on current valuations. The key issue is not what equities have done relative to bonds in the past but what their potential is going forward. Experience tells us that these two concepts can move in opposite directions.

The historical (or ex post) equity risk premium

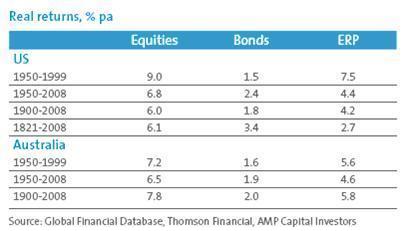

Many analysts tend to focus on historical data as a guide to the type of return premium investors require for shares over bonds and to what it will be in future. However, while a useful starting point, this approach has limitations. Firstly, the historically realised return differential between equities and bonds varies signifi cantly over time. As can be seen in the next table, between 1950 and 1999 the ERP was 7.5% pa in the US. However, if the period is extended to 2008 the ERP falls to 4.4% pa. Similarly the realised ERP for Australian shares was 5.6% pa over the 50 years from 1950, but if the period is extended to 2008 it drops to 4.6% pa.

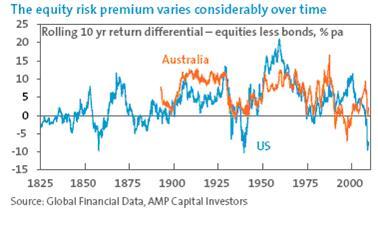

The instability of the realised ERP is highlighted below. Over rolling 10 year periods the excess return from shares over bonds has varied from around -10% to +20% pa in the US and from around -7% to +17% pa in Australia. So the negative or low equity risk premium over the last decade is not unusual in an historic context. It is also of interest to note that there is a degree of mean reversion in the chart, with decades of low excess returns from shares being followed by decades of high returns, and vice versa. So, the poor performance of shares versus bonds over the last decade actually suggests there is a good chance of shares outperforming bonds over the decade ahead.

Obviously, the starting and end point valuation for markets for any period can heavily affect the size of the realised risk premium, even over long periods. For example, over the 50 years from 1950, bond returns were reduced due to low bond yields. As such, bonds suffered capital losses as yields were much higher in 1999. Against this, equity returns were boosted because shares were depressed relative to earnings in 1950. This lead to strong capital gains over the next 50 years as share prices rose relative to earnings. As a result, over the period between 1950 and 1999 shares outperformed bonds by a very wide margin. However, by changing the end point to the end of 2008, the return from shares has been greatly reduced. Mainly due to the recent bear market and because bond yields had fallen sharply boosting the measured returns from bonds. The point is that even when measuring over long periods the starting point and end point have a big impact on the measured equity risk premium.

Secondly, to the extent that valuation changes boosted the realised equity risk premium over the post-war period, this would have not been expected by investors and hence the measured ERP over that period is not a good guide as to what they would have required to invest in shares. Furthermore, it is diffi cult to justify why investors would have demanded such a large premium as this would imply an implausibly high degree of risk aversion. Finally, historical equity data for countries like the US and Australia suffers from a survival bias. An investor who bought into German and Japanese shares in 1900 would have been wiped out along the way.

For these reasons, while an analysis of the past is a good starting point it does not provide a definitive guide as to what the equity risk premium should be or will be.

The required equity risk premium

We have already noted the historically realised ERP is poor guide as to what investors actually require to invest in shares. The 5% to 7% ERP achieved in much of the post-war period was in large part due to a windfall gain to equity investors they were not expecting or requiring. Several considerations suggest that the required ERP has fallen and is now well below this, including:

• the fall in inflation which has likely resulted in a higher quality of earnings and reduced economic uncertainty;

• a greater feeling of global political security – no major wars in 60 years and the end of the Cold War;

• improved regulatory and legal protection for investors;

• lower trading costs in equities, greater scope to spread risk via diversification & improved market liquidity; and

• increased demand for shares from pension funds helped by tax concessions on retirement savings.

While the ‘war on terror’ and the global financial crisis may have partly offset some of these favourable factors, the broad trend is still positive and suggests investors should demand a lower risk premium than 50 years ago. Our assessment is that the appropriate equity risk premium going forward for US and World equities is somewhere around 3%. For Australian shares, fewer opportunities for diversification justify a slightly higher premium of around 3.5% and for Asian shares greater economic and market volatility suggest a required ERP of around 4%. However, while this is our assessment for the required return differential for equities over bonds, what will actually be delivered going forward is a different matter.

The prospective (or ex ante) equity risk premium

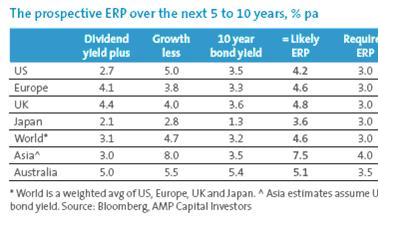

A simple way to think of the prospective (or likely) ERP for the next five to ten years at any point in time is as follows:

Likely ERP = Dividend Yield + Growth Rate - Bond Yield

The Growth Rate is the growth rate in share prices and this is assumed to equal the long-run growth rate in listed company earnings. This in turn is assumed to equal long term nominal growth in the economy. This approach makes intuitive sense as the return on shares equals dividend income plus capital growth.

The table below provides current figures for each of these, the prospective ERP in the second last column and for comparison purposes our estimate of the required ERP in the final column.

This suggests that likely ERPs for shares are now well above what we think is required. This is particularly the case for Asian shares. Thanks to the slump in shares since 2007 which has boosted dividend yields and the fall in bond yields, these estimates are far more attractive than was the case in 2007 when the last cyclical bull market peaked, bond yields were much higher and when Australia offered a prospective ERP of 3.6% and the US 2.5%. Note that the above calculation of the prospective risk premium assumes that bond yields are unchanged. In fact the risk over the next few years is that bond yields rise towards more normal levels as central banks raise interest rates and inflation increases. This will result in capital losses on government bond investments and hence a potentially higher excess return from shares over bonds.

Conclusion

1. The historical record does not provide a definitive guide to the risk premium that shares should or will offer over bonds. Just as the recent experience of a negative excess return understates the return from shares over bonds, longer term perceptions of a 5% to 7% pa return excess exaggerate it;

2. A range of factors suggests the required ERP is somewhere around 3% to 4% pa;

3. Current estimates suggest the prospective ERP is now above this level, particularly for Asian and Australian shares. The prospective return differential offered by stocks over bonds today is far more attractive than it was at the height of the last bull market in 2007. While stocks are vulnerable to a correction after their sharp gains from March, their attractive risk premium compared to bonds suggests that any short-term pullback in shares will simply be a correction in a still rising trend.

Dr Shane Oliver Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist

AMP Capital Investors